The Agony and Ecstacy of the U.S. Government's Relationship with Apple's iPhone, Part 1

The recent chaos from new tariffs following Liberation Day is not the first time the U.S. Government has struggled with Apple...I was there Gandalf...

*Updated with statistics about the 1102 workforce and government spending.

All thoughts, opinions, and other words here are exclusively the personal opinions of the author and do not express any official position, statement, or other communication from or on the behalf of the U.S. government. This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead or actual events is purely coincidental.

In 2011, I joined the U.S. Government as a job series 1102 - Contract Specialist - at the U.S. Census Bureau. A contract specialist is supposed to be the actual, professional expert in contracting. Many people who claim to be “government contracting experts” have never actually held a “warrant” or bought anything for the government. For folks like me, listening to people claim expertise or offer contracting insights—and you’d be amazed at how many of those people there are after-the-fact but never in the trenches dealing with this—sounds and feels a lot like this (1102’s are Kareem for this analogy):

The idea of a “warranted contracting officer” arose out of the U.S. Civil War. That war caused an unprecedented increase in contracting activity—and fraud. The War Department kept having people show up with “signed” contracts from the government demanding payment. The government couldn’t keep track of what was legitimate and what was not. So Congress decided to create an official government position, also known in government as a “single throat to choke,” who would be the only person able to legally bind the government to a contract.

Individuals who were issued a “warrant,” like a Letter of Marque that made a pirate into a legal “privateer” for the government like some of my ancestors, were tasked with:

- getting the “best deal” possible for government spending by;

- promoting competition and fairness for industry;

- preventing fraud, waste, and abuse (for real not just saying it there’s an actual legal definition for this not just a soundbyte);

- enabling agency missions; and,

- complying with any and all other laws, judicial rulings, executive orders, departmental directives, agency policies, or other other shit they can throw in there from Congress or anyone else above you in the command chain about what, how, where, when, why, and how to spend taxpayer money.

It’s an impossible job description and legal responsibility. Terrence O’Connor’s book Understanding Government Contract Law describes the contracting officer’s role as “Judge, Sheriff, Defendant, and Plaintiff” all in one. If they’re fully aware of this fact and know what they’re doing—and many 1102’s understandably check out or give up but stay in the role—then that 1102 is on high-blood pressure medication, may have a drinking problem, or something else. Happiness in 1102’s is the rarest thing I know.

I got into this because I was looking for a new job following the first Great Recession of my life right after I graduated law school and passed the bar exam—but there were no jobs for lawyers. All of my prior experience was in non-profits.

A friend of mine observed, “Well you’re a lawyer and you like conflict so you should get into government contracting.” Oh boy, were they not wrong.

And so I went to USAJOBS.gov and started applying to positions. Eventually, I was a “direct hire” as a GS-9 1102 Contract Specialist at the U.S. Census Bureau in the Department of Commerce.

The 1102 job series is a “direct hire” position that allows agencies to circumvent and expedite a lot of federal human resources (HR) rules. In 2011, contracting was the only job series that allowed for this across the government, cybersecurity specialist has since been added.

The direct hire exemption for the 1102 job series exists because it has been in crisis since the Clinton administration—when the acquisition workforce was gutted as part of a major reform initiative resulting in tens of thousands of contracting officers, price specialists, and other acquisition professionals across government being let go.

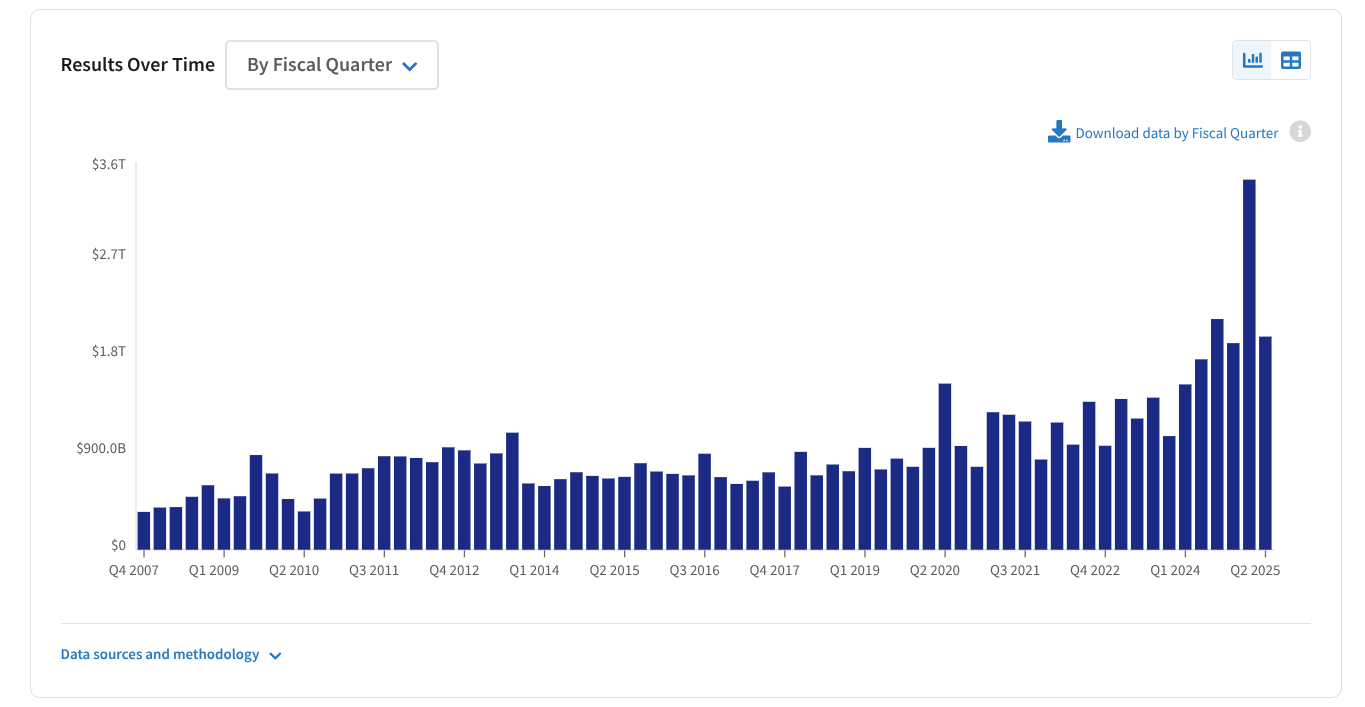

Why? Well, government was going to be “more like industry” so it didn’t need this professionalized buying workforce—we would “buy commercial” instead of the infamous $600 hammer. Buying commercial actually increased contracting actions, not only by total dollar amount but in the number of annual transactions. This reduction-in-force (RIF) coincided with an explosion of government spending, specifically in outsourcing through contracts.

To the point of just how gutted the 1102 workforce was, pre-DOGE, look at this study from 1991 (Pre-Clinton purge):

There may be no area where there has been greater concern about the quality of Federal workers and the work they perform than in the procurement of goods and services from the private sector. During the 1970’s and early 1980’s there were several highly publicized incidents which involved questionable Federal spending. Employees responsible for Government procurements were severely criticized for spending too much money to purchase a variety of products ranging from coffee pots to major weapon systems.

As a result, the Government instituted a number of changes in the procurement process which were intended to reduce the probability of abusive spending. These changes included increasing the number of people working as contract specialists. The intent was to reduce the pressure and responsibility for procurement actions that would be placed on any one person. The net effect was a 61 percent increase in the number of people employed in full-time permanent GS-1102 procurement positions between 1980 and 1991 (from 19,409 to 31,287).

In 1991, there were 31,287 of my brethren. In 2017, the General Services Administration (GSA) conducted a study to look at the rate of transfers of 1102 across different agencies:

In order to better understand the magnitude of GS-1102s leaving one agency to transfer to another, the transfer out rate for the GS-1102 population was calculated across five fiscal years. As demonstrated in table 3, the GS-1102 occupation series had a transfer out rate of between 4% and 5% between FY 2011 and FY 2015. In comparison, the governmentwide transfer out rate (exclusive of GS-1102s) was approximately 1% for each year. During this period, the population size of the civilian GS-1102s remained consistent between 12,400 and 13,000 members.

Show me a functioning organization that loses more than half of its workforce.

I cannot imagine how bad it is going to be at the end of this fiscal year post-DOGE.

Dramatically reducing the work force while at the same time dramatically increasing the very specific work load that just reduced work force was uniquely capable of handling is a real 4-D chess move.

I'm sure this is part of the strategery, and it may explain why GSA has started frantically hiring back more 1102's after the first wave of DOGE-purges.

The alleged rumor is that GSA has lost over 40% of their 1102's since January 2025 right when they told everyone they're going to be doing more buying than ever.

But you know Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) has totally become sentient and can replace learned professional experience from humans with critical pedagogy...

Anyway, if you’re reading this and don’t know what the U.S. Census Bureau is—you should.

The U.S. Census Bureau measures America’s people, places, and economy. But it is most well known for the “Decennial Census of Population and Housing.”

The U.S. census counts each resident of the country, where they live on April 1, every ten years ending in zero. The Constitution mandates the enumeration to determine how to apportion the House of Representatives among the states.

Every 10 years the average person is reminded the Census exists…

The Decennial Census, or “decennial”, is often billed as the largest peacetime operation of the U.S. Government. Given the scale of it, it actually is the government’s largest non-military operation.

Typically, for the past couple hundred years, the Census will hire thousands of temporary workers, now around half a million of them, to go “door to door” to count everyone once (for more go find the West Wing episode “Mr. Willis of Ohio” that explains why we have to do this instead of statistical sampling).

It sounds simple. But…it turns out that counting everyone in the U.S., including outlying territories and islands like Guam, is incredibly complicated.

There have been 24 decennial surveys in America’s history. And it has always been delivered to Congress as mandated by the Constitution on time (this is a point of pride for Census federal employees and contractors).

Of those surveys, 23 of them have been done on paper.

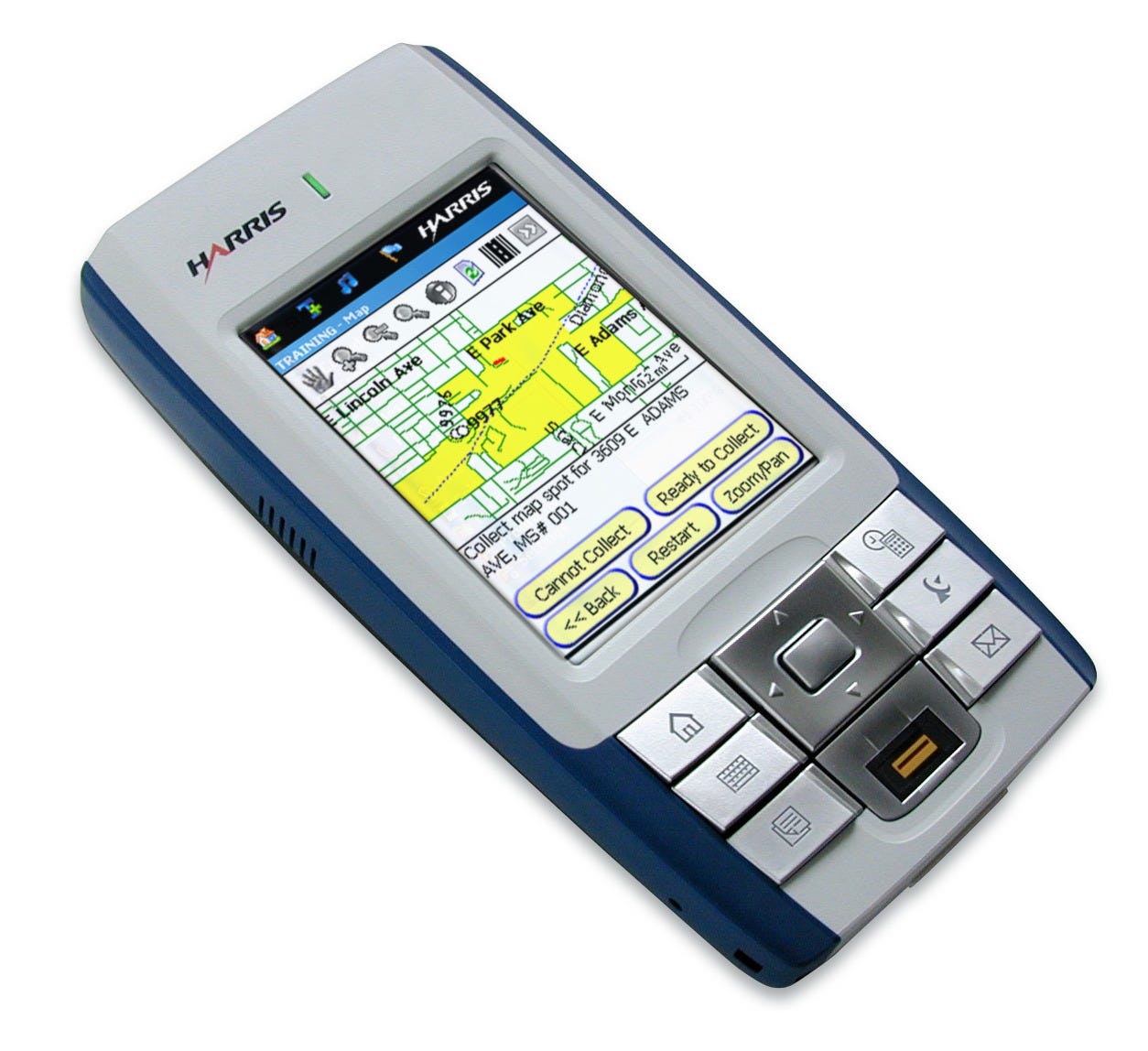

The 2010 decennial census was supposed to be the first “digital” census using a “handheld computing device” instead of a paper form.

This program was called—Field Data Collection Automation (FDCA).

TL;DR the bureau tried to create its own iPhone before there were iPhones using windows mobile, meant for personal digital assistants (PDAs), and custom built hardware. Of course, being the government and given the state-of-the-art at the time, this meant we relied on the military industrial complex to create these things.

The FDCA program began in 2001, Census was now developing a first of its kind personal computing device (not that much of a stretch in government procurement history). Over the next several years, the bureau went through intensive prototyping and testing, major software development, and actually manufactured several hundreds of thousands of FDCA hardware units.

But then out of nowhere, the iPhone was launched in 2007 rendering years of work on FDCA, and all other mobile hardware, obsolete. It was a whole new class of device.

But, it was too late logistically, contractually, and operationally to “just switch” to using an iPhone, like many Congress people would insist during hearings after 2010 (but holding one up and asking that question like drunk uncle makes for a great hearing snippet).

To make matters worse—due to software development issues—FDCA had to be scrapped at the last minute and the 2010 Decennial was done using its backup plan—paper forms.

It’s too long of a story to get into, suffice to say that—before healthcare.gov—it was the single “greatest IT project failure” in government procurement history.

For context, 90% of government IT projects over $10 million dollars fail — so really this was just a normal day for the government.

But it was a huge scandal! Opinion articles, Congressional hearings, thought pieces, and shame—oh the shame—followed.

As this period was wrapping up I, blissfully unaware of all of this at the time, became the third person added to an informal team of 1102’s who would do all the “Decennial Information Technology (IT) requirements”—meaning billions of dollars worth of hardware, software, professional services. Major systems. Big stuff.

Again—the Decennial has always been done completely and delivered on time.

We were tasked to “not let that happen again” for the 2020 Decennial—which would be the first non-paper decennial survey. Cue Queen’s “Under Pressure”.

Census had this confidence because FDCA was hard. Fortunately, industry had made it easy with these “smart phones” (ironically they relied almost exclusively on government funded research and development (R&D) just like Apple had done with Xerox’s R&D for personal computers). Sidenote, Census employees who were part of or around during FDCA still refer to “smart phones” as “hand helds.” It’s weird.

Planning for a decennial census starts decades before it happens, there’s currently a 2040 planning office. When I started the job in 2011, there was already cross-functional, cross directorate, bi-weekly meeting for all 2020 Decennial contracting needs. It had already been underway for a year.

Now given what the Decennial Census really is at its core—data collection, processing, and dissemination—about 80% of Census Decennial spending is for IT (Census actually has a huge historical role in the development of computers and was at the vanguard of the science at one point in time).

And so, because I was also a “lawyer,” I was handed:

- a copy of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR),

- a 3” thick binder of material from this meeting so far, and

- sent to this planning meeting to deal with anything that comes up.

For those readers who were not really around or aware of what the vibe was like in tech and government in the early 2010’s, you must understand that Steve Jobs—and Apple—was revered like the Beatles and Jesus. Apple products were short-hand for “bleeding edge” and “in the know.” Apple was cool (and misogynistic or whatever the joke is here?).

Shiny, silver metal over black or beige plastic.

I had to regularly deal with people who would purposefully dress like Steve Jobs and/or be “jerks” to emulate his aesthetic.

Now in 2011, despite the iPhone’s popularity and being on it’s 4th iteration at this point in time, the U.S. government used Research in Motion (RIM)’s Blackberry—not the iPhone.

For a number of reasons, the government is usually 2-4 years behind whatever is happening in the mainstream. Recession in 2008? For government agencies, that was felt as “sequestration” in 2010-2013. Cloud computing for consumers around 2010? That’d start showing up in 2013 (that’s a whole different story, again I was there).

This chronological lag especially shows up for consumer technology which largely overtook government tech right around this time in terms of computing, “big” data, etc.

Everyone. EVERYONE in government wanted iPhones, sometimes Samsung’s competing Galaxy line, instead of their government issued BlackBerry. Again, because Apple was cool.

If you saw a government CIO at the time, you would forgiven for thinking they had contracted a fatal case of rabies whenever iPhones came up due to the copious amounts of saliva dripping from the corners of their mouth.

Unfortunately, despite this rabid exuberance, the U.S. Government could not legally buy iPhones. Technically, it still cannot legally buy them.

In fact, the U.S. Government could not legally buy any Apple products. There were two primary blockers, one technical and one legal.

First, there was a software issue. There always is a software issue because everything’s computer. The BlackBerry’s backend was already fully integrated into agency’s email systems, Virtual Private Networks (VPNs), etc. So it was a huge technical lift to swap out the end points from a BlackBerry to an iPhone (especially because Apple did not really care about enterprise-grade techstacks at this point in time so their own software was a “take it or leave it” for both industry and government customers).

This is known as a “switching cost” and you will usually see it cited as a reason why government will have to “sole source,” meaning there’s no chance for someone else to bid on it, a contract for something and also the primary goal of contractors when creating “vendor lock-in” (don’t worry we’ll get there).

Second, and this is where tariffs and protectionary trade measures arise, there is a legal issue. As mentioned above, the U.S. government can’t legally buy an iPhone.

Why can’t the U.S. government legally buy iPhones?

Like most things—because of Congress—specifically because of two different, but related laws passed by Congress half a century apart.

Those two laws are The Buy American Act of 1933 (BAA) and the Trade Agreements Act of 1979 (TAA). The way that these two laws work in conjunction is through an arbitrary dollar threshold. That threshold is set through the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s, which the U.S. is a member of, Global Procurement Agreement (GPA). It usually hovers around $200,000.

One of these two laws will always apply to any government purchase.

If the BAA does not apply, then the TAA applies. These two laws are a draconian measure—counter to “free trade” principles—to force the government to only spend taxpayer money with American businesses or America’s friends (the BAA was a reaction to Great Depression and the TAA was a reaction to the Oil Crisis of 1973 and other geopolitical hiccups during the 1970’s).

However! Thanks to the efforts of the George W. Bush administration, an exemption was created for “commercial IT” below the WTO’s GPA threshold—around $200,000. This exemption was passed into law and allowed government agencies to buy “commercial IT” products under the arbitrary dollar threshold—any purchase above that BAA threshold would be subject to the TAA.

This restriction exists irregardless of any additional tariff that may or may not be enacted.

China is a member of the WTO but the U.S. does not have a trade agreement with them. That seems odd considering just how much we buy from China as a nation—I don’t understand it and apparently no one else does.

This means that a U.S. government agency was, and still is, only legally allowed to buy up to $200,000 worth of whatever commercial IT—meaning Chinese made—product they want. And given Apple’s current retail price for any of their products—that is not a lot of units.

As was, and has been, the case since I began my government career—iPhones and almost all Apple products—are almost entirely made in China. One of my favorite data points out there today is that if an iPhone was made in the U.S., rather than just being designed here, it would cost upwards of $30,000 per unit.

As a buyer for the U.S. government, made in China is verboten, very bad, do not buy, put down the pen and step away.

If you break this law, Congress will be pissed off. And no one likes Congress—the group that created 1102’s in the first place—when it is pissed off. Especially at you as the career civil servant who signed your name on a document legally binding the government to something that is illegal.

We are supposed to be buying things with the money Congress gives us based on the rules they attach to that money (fiscal law). Otherwise, we’re breaking the law.

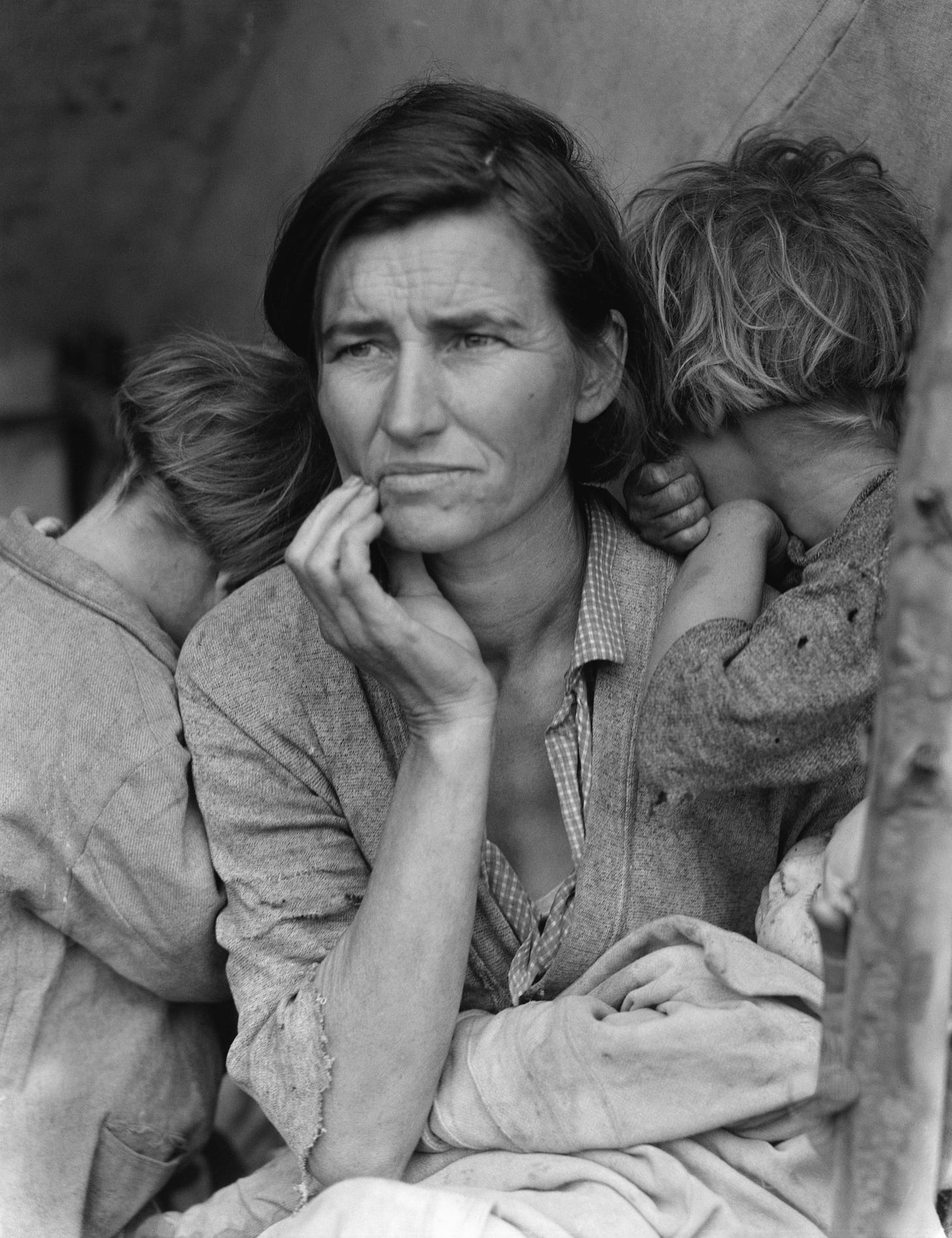

And so, while attending my very first meeting of the cross-functional, cross-directorate 2020 Decennial acquisition planning meeting as a freshly minted 1102—I was told that we would have to get ready to buy at least 500,000 iPhones for “door knockers” (this is a slang term used for temporary and other field staff who actually physically conduct Census surveys like Decennial).

My immediate thought having spent a considerable amount of time figuring out everything I just shared above was…

How in the hell am I supposed to do that?

What followed, I could not have possibly imagined happening, but it did.

Stay tuned for Part 2.